BIRMINGHAM / MONTGOMERY – It’s been a nonstop week. Meetings with three different lawyers, a prison visit, court, two trips to the state archives… I also went to the Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham and the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery. As soon as I arrived, I knew these last two places would require a post in their own right. Now I’m wondering how to describe them: they undoubtedly attract tourists, but I couldn’t call them tourist attractions. “Education centres” is closer to the mark, although there are many reasons beyond just education for visiting. For me, BCRI and EJI’s impactful documentation of racism in America provided highly relevant context for 3DC’s cases involving race and the criminal justice system today.

Birmingham civil rights institute

The Civil Rights Institute is a circular building in downtown Birmingham, with pale steps leading up to it and a domed metal roof. A tall statue of Martin Luther King Jr stands outside, with quotes from his most famous speeches on its base.

You walk inside and turn left, into a section on segregation under the Jim Crow laws. Two water fountains stand next to each other: the taller one with functional-looking taps has a sign saying “whites only”. The one marked “colored” is a foot shorter, made of cheap materials that seem deliberately chosen to crack and rust. There’s also a side-by-side recreation of “white” and “black” classrooms as they were in the 60s and 70s, showing a similar level of manufactured disparity. The first classroom has comfortable chairs and a state-of-the-art projector; the second has hard stalls and a scratchy blackboard.

A mining cart stands in the corner. Post-abolition, the only jobs available for many of industrial Birmingham’s black population were in its steel works and coal mines. Having recently entered the museum from the suffocating heat outside, you might imagine how long you’d last if you were labouring here by a furnace in a sooty boiler suit during summer.

The next section of the museum shows a display of racist objects: posters, dolls, cartoons, and kitchen utensils covered in slurs and caricatures of black people. A Klan costume in a glass case completes the wall, looming out of the dark at the end of the corridor.

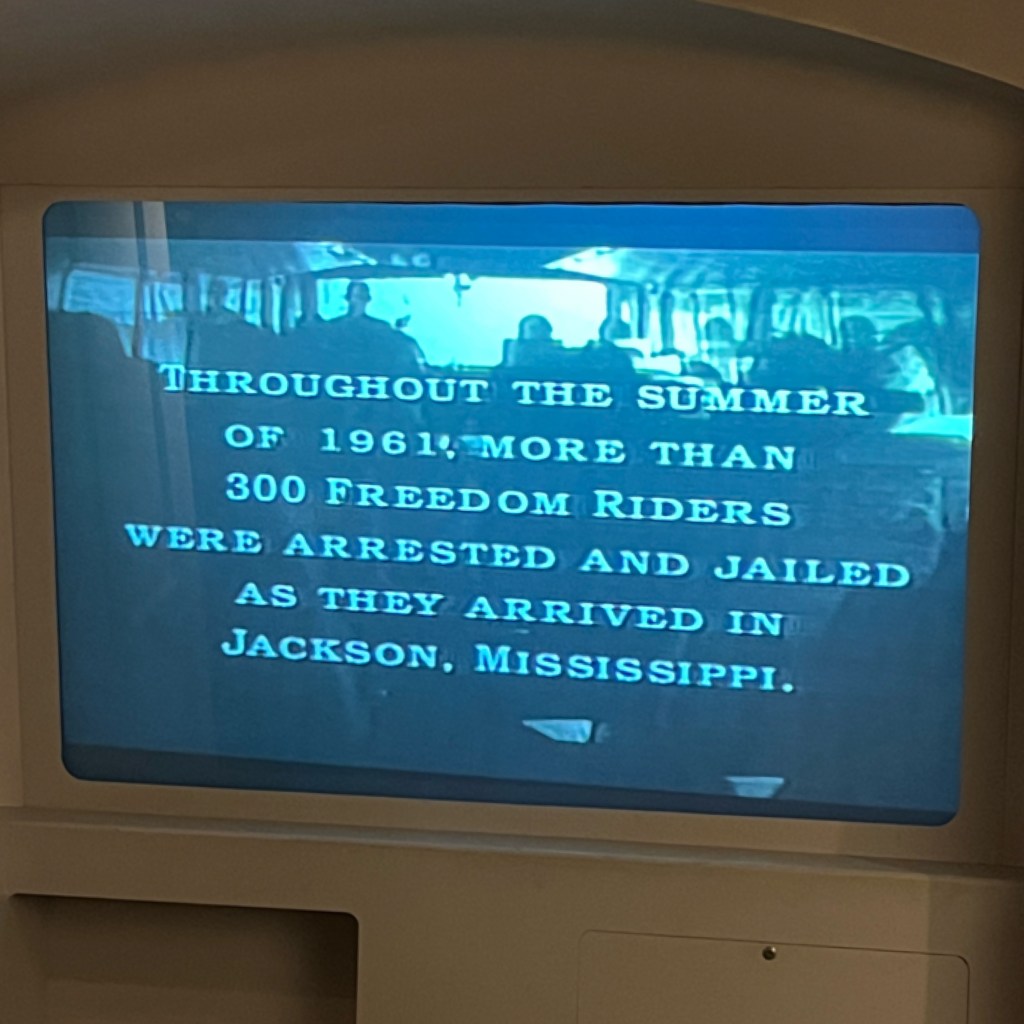

Then you enter a hallway dedicated to the Freedom Riders, with a screen showing old news broadcasts about the attacks on their perilous journeys across the South. There’s also a smashed window from the original Greyhound Bus; from asking a number of visitors about their impressions, this section seems to stand out in particular for white people.

Everything about it asks: “If you were lucky enough to be white in the 1960s, would you really have got on that bus, most likely for no personal gain beyond the feeling that you’d done a little bit to address inequality? Or would you have kept yourself away from mortal danger and counted your blessings that said inequality wasn’t designed to disadvantage you?” It’s not a pleasant question.

The rest of the museum follows the history of the black vote, the eventual (often merely nominal) progress of equal rights and simultaneous retaliation from white communities. Then you round the corner and see the 16th Street Baptist Church through a large window, the target of the 1963 bombing. The final display includes the tools used by the KKK to plant the bomb, and a fragment of stone removed from the skull of one of the four girls killed in the explosion.

When you walk outside, you can see the church fully and a memorial to the bombing victims in the park across the road, along with a larger-than-life metal statue of snarling police dogs.

EJI: The legacy museum

Located in central Montgomery, the Legacy Museum was opened in 2018 by EJI, a human rights organisation founded by defence lawyer Bryan Stevenson. Its scope is boarder than BCRI’s, because it takes in a longer historical period, showing the direct progression from slavery to the situation today.

On entry, you’re immediately confronted by a moving floor-to-ceiling graphic of the sea. The crashing, stormy waves will probably induce motion-sickness if you look at them for long enough. Around the edges of the room are screens with infographic animations, showing the passage of slave ships across the Atlantic over time, and statistics of how many Africans died during the voyages.

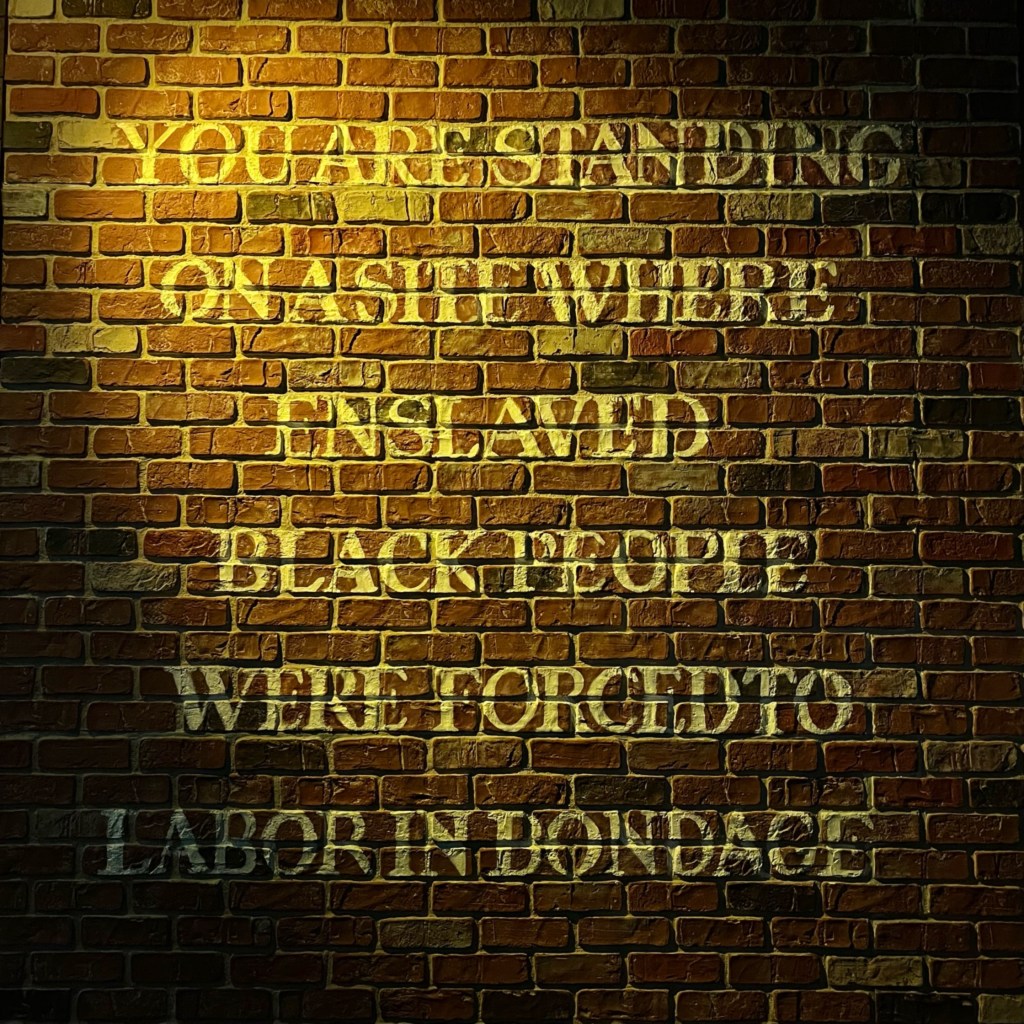

Walking through to the next room takes you down a dimly-lit corridor, where clay sculptures of agonised, drowning faces cover the floor on either side, depicting the thousands of slaves thrown overboard. Then you reach a series of paragraphs on the wall, explaining the slave trade’s role in America’s development.

The displays are heavily based on testimony. The next section about slave auctions is built around a wall covered in quotes from dealers, observers, and slaves separated from their families, all carefully selected from original records. You then progress through a room painted with timelines and further witness statements, giving soundbites about life on plantations and the brutality faced by second-generation slaves.

Then you reach the section on lynching, based around a collection of graphic photographs, newspaper clippings, and a wall of urns filled with soil from where murders took place. You’ll probably be struck by the aura of pageantry recorded at the time – rather than being a system of killing which authorities had any incentive to keep hidden, the lynchings catalogued at EJI were intended to be as widely-publicised as possible. In a mob-driven, state-tolerated terror campaign (incompletely documented), there were enough known incidents for EJI’s interactive map to pinpoint the locations of over 4400 racial killings across the USA between 1877 and 1950.

On to civil rights – this is a condensed version of the time-period explored by BCRI. There’s information on Martin Luther King Jr, Malcom X, Rosa Parks, the Freedom Riders, the vote. There’s certainly a lot of history to get through for a country that’s been around such a relatively short time… You have the opportunity to try the “IQ test” which black people in Alabama had to pass within three minutes before registering to vote. Questions include: “How long is a piece of string?” and “How many seeds are in a watermelon?”, as well as obscure trivia about the US constitution. No matter where you’re educated, it’s designed to make you fail. Whoever wrote it seemingly intended to humiliate anyone optimistic enough to believe that the system would henceforth act fairly.

In fact, this message underpins the rest of the museum. It takes on the feeling of a 3D essay, arguing that the suppression of black people in America hasn’t abated but simply adapted to exist in socially acceptable ways – ways which are now harder to see amid superficial demonstrations of progress. EJI also points out that slavery may have been abolished in the mainstream, but is still permitted under the 13th Amendment for those found guilty of crime…

The final room follows the development of America’s prison-industrial complex, exploring reasons for the disproportionately high representation of black people in the prison system. Driven by the “war on drugs”, unequal sentencing, police brutality, and many other factors, EJI shows how black and brown people are still the most likely to perform unpaid labour behind bars.

When you exit, the Legacy Museum comes with a bookshop, rather than a gift shop. It stocks a carefully-compiled collection of both fiction and non-fiction books about race.

A few blocks away is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, also set up by EJI. After walking uphill in the beating sun to reach it, you’ll probably be glad to step undercover beneath the memorial’s long, open-sided roof. Then you look up at the names of all known lynching victims, arranged by American county, stamped onto ranks of human-sized metal boxes hanging in the air.

Together, BCRI and EJI are unlike any museums I’ve been to. For one thing, “museum” isn’t a word I’d use, especially not in the British sense. Instead, they’re immersive experiences, visually and architecturally designed to make reading people’s quotes and engaging with their memories as interesting as possible. And by reading, you learn a lot. If you ever end up in Alabama, I’d highly recommend a visit.