WORKING FROM HOME – It’s raining again in Vestavia Hills. Every afternoon this week we’ve had a torrential downpour with thunder and lightning, which stops and dries up in the sweltering heat later on. But that’s okay, because the work’s begun in earnest. When we’re not out on location, the 3DC interns set up in the home-office of the lawyer they’re helping, drafting letters and taking calls. Now I’m going to write as much as I can about their handling of active cases. What’s their methodology? And what it’s like to call a client who’s a convicted murderer?

Yellow Pages

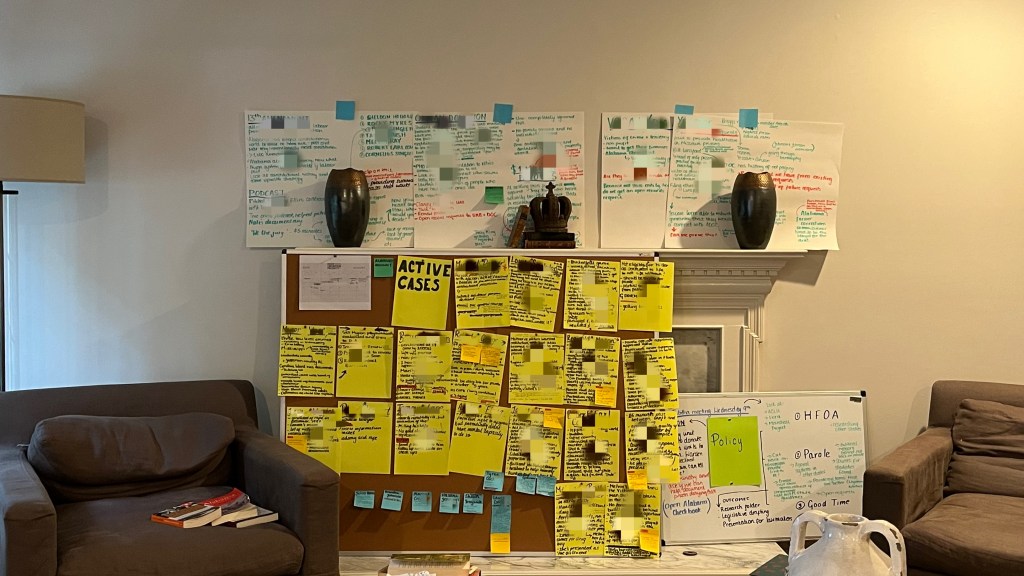

3DC’s interns start by sitting down with L. (the lawyer) and talking through the facts of every case where she’s asked for assistance. There are fourteen of these, so it takes a while, and Millie notes down key information on yellow pieces of paper, pinning them up on a noticeboard.

Some of L.’s clients are being abused by prison staff and need help moving to alternative facilities. Others are up for parole, seeking resentencing, or trying to appeal their case.

Every time a new client’s added to the pinboard, I make a point of looking them up on the ADOC (Alabama Department of Corrections) “Inmate Search” tool, to see exactly who we’re dealing with. At first I was surprised by the amount of information openly accessible on a public database; height and weight at the time of incarceration, detailed descriptions of any tattoos, past criminal record, headshots…

Most of L.’s clients have the abbreviations DR (Death Row), LW (Life without parole), or LP (Life with possibility of parole) by their names, and an average sentence length of 999 years.

Once we’re acquainted with their cases and needs, the interns write action points for each client, to follow through in the coming days. Most of these involve paperwork… filing and signing letters on an inmate’s behalf is a big part of the job. Requesting trial transcripts from courts so their appeals can be added to county waiting lists is another.

Getting hold of these transcripts can be a saga in itself. Because appeals in Alabama are made on the grounds of procedural failings or overlooked arguments from a defendant’s initial trial, it’s essential for their current attorney to have their original court files. However, the files from “live” cases (where an inmate’s now inside) are difficult to obtain, as clients frequently lose them in post-trial prison transfers. A lawyer can re-request them from the court, but often for a heavy fee… One of L.’s clients has to pay $1400 to access his court files.

“Why’s it so expensive to get record of your own trial?” I ask, aware that many inmates won’t have this sort of money. “They have to be authenticated by authorities before we can use them,” Clara tells me. “The charge covers scanning, stamping, posting and verification. It can be $1 per page for files of over 1000 pages. It’s scandalous.”

dialling in

Midway through the day, L. needs to call a prisoner to check some facts about his case. He was convicted in 1984 for murder at the age of eighteen and has been in prison ever since, parole denied. He’s nearly fifty now.

Everyone has the chance to speak to him, and I’m struck by how normal our conversation is. The line’s crackling and there’s background noise from other prisoners, but he sounds casual, as if he’s calling from anywhere else in the world. He answers our questions about the night of his crime calmly and respectfully – doubtless a story he’s told many times.

I wonder what it’s like to be going about your dull routine in prison and then suddenly have to relive your darkest moments for a group of legal assistants on the phone. But one thing’s for certain – most inmates are so bored that they’ll take a call about almost anything, just break up the day a bit.

As we reach the end of our questions, the prisoner on the line becomes more impassioned. We’ve asked if he’s able to pay to access his court files; he says he has people who’ll find him the money. “I want to get out of here and never want to come back,” he insists. “I want to be free to go outside when I want and do things when I want. Once I’m out, I’m out. I’d never do anything to go in this system again.”

I wonder how these words would come across in court. Would a judge see it as spiel? Just talk? Or would they consider how a man who’s been inside since eighteen might place a different value on freedom than someone who’s been in and out for the last twenty years? Every case is different.

After the call, I ask the interns about their experience talking to incarcerated people. They all say it humanises clients, but have different views on whether this is a beneficial thing.

“I think it would be too overwhelming to have a full-blown, personal relationship with the people on all those yellow posters in the living room,” is one argument. Phone calls are okay, but some of the interns think they can be more effective as lawyers by processing letters, numbers, and transcripts without putting faces to the names.

Others say that having a close, human relationship with clients is the best way to understand their cases, needs, and motives. “It’s easier to advocate for someone whose upbringing and mental health you’ve really thought and talked about.”

I consider this and one thing’s for certain: it’s emotionally taxing work, but if a defence lawyer doesn’t humanise their client, the state isn’t going to. I’d be interested to know what other people think.

The week beyond this has been varied – I’ve witnessed parole hearings, met with a former Attorney General & sat in on a meeting for death-penalty reform lobbyists. Tomorrow I’m meeting with the head of Alabama’s Sentencing Commission, and the interns have been making significant headway in the Montgomery archives, finding new evidence for the Post-Mortem Project. Stay tuned, more to come…